The snapshot...and beyond

One part of the world wide web experience is the ability to wander aimlessly, linking from one site to another, until the wanderer ends up somewhere completely previously unimagined. Somehow recently, when looking at photographs at the Flickr site, I came to a photo that expectedly stopped me in my web-surfing tracks. Understand, please, that being caught up short by a photo is not unknown to me. I look at many photos, so I see many good photos--and, also, not a few that are mediocre or worse.

A quick word first about those photos that are less than "good." Having seen numerous on-line arguments about what is (or is not) art, I have little interest in sparking another episode of that unresolvable debate. Let us try to agree though, that there exist many photographs that, for some reason, do not prompt much of a response in most viewers. Whether it is because the subject matter is uninteresting, the treatment (composition, etc.) is unoriginal, or because the technique (focus, exposure) is lacking, such photos leave us with a dull, flat feeling. While an occasional photograph might even provoke irritation, most of the time when a photo is "not good" or "not artistic," it simply does not connect with most viewers.

A number of writers maintain that the shortcoming of such photographs is that they do not connect emotionally. I've never been entirely convinced that the failed connection is an emotional one. Sure, I've seen many excellent photos that stir my emotions, but I've also seen many excellent photographs that elicited interest, admiration, intellectual curiosity--you name it. In other words, some photos create a many-faceted response, yes, but it does not seem to be a requirement that one of those responses is emotional. (That's unless, of course, you want to count that tinge of excitement and satisfaction at having discovered something excellent. Certainly that is a delightful feeling, one that is regrettably rare, but it is not the same thing as feeling an emotion based on the photo itself.)

However, something about this particular photo grabbed me in a way much different from the good/not good or artistic/not artistic categories that other photos seem to sort themselves into. This photo, as far as I could see, was good, and it was artistic, but yet it did not seem to make any pretense of any effort to be those things. Instead, there it was, masquerading as a simple snapshot. Why was I staring, unable to look away from it, my mind racing as I looked into it and thought I saw more and more?

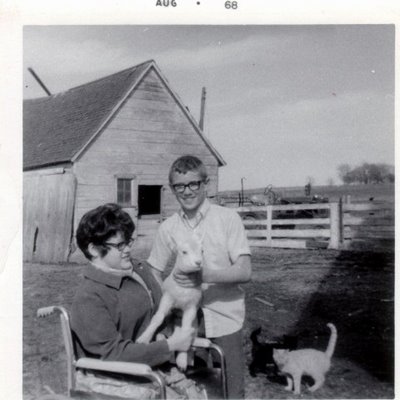

Enough suspense, here is the photograph.

What I know about the photo is, purposely, little. I emailed the person who had posted it at her Flickr site, and in granting her gracious permission for me to present it here she noted that she had not made the photograph, that it was probably made by her grandmother or late great grandmother, and that the photo had been made at their family farm.

Even without those bits of information, one thing we know about the photo at first glance is that it has a narrative context. Narrative context is not a requirement of a great photo. Adams or Weston can show us a mountain, a rock outcropping, a tree, even a pepper, and the genius is that they have seen it so intently, so completely, that they empower us to see it in the same way. However, unless there is some anecdote connected with the making of those particular photos, there is little narrative context to such work. It is enough that such photographs seem to say "Look here. See this, and for a moment see only this, in a better way than you've ever seen it before."

This "snapshot," on the other hand, has narrative context in spades. We sense that the people seem to know each other well. We sense that they could be related (and guess that before seeing a title--Uncle Jim--which might support that guess). Now our eyes are racing about the photo to see whatever else we can find. The woman's wheelchair catches our attention, and our minds cannot help but note that something other than age has placed here there, for she is a young person in a wheelchair. There is more than an implied connection between the two persons, because Uncle Jim is helping the young woman hold an animal (a lamb?). It is, literally and figuratively, a living connection between them.

The scene is rural. There is a barn, a wooden fence, a tractor. We seem to be seeing people in a scene that is on the edge of an expanse of open land. There is a stand of trees on the horizon line, and perhaps there is something (another building?) behind those trees.

While objects such as the barn and fence are fixed, the scene is fluid rather than static. The young animal, carefully held, could bolt and run. Walking about are a cat and another animal, probably a second cat. The humans, like people in any photograph, give the impression of being there only in that specific instant, temporarily. In just a few seconds they are likely to move out of the frame of the image...and into the rest of their lives.

Words always fail to represent art adequately, and the picture holds other powers we have not yet attempted to approach. A shadow invades from the right and provides a dark area (foreboding as time itself, if you want to see it that way), and the shadow line is a strong diagonal connecting the people (the photo's immediate present) to the horizon (everything else, seen and unseen). The shadow line passes right over the cats--one light, the other dark--who overlap one another into a kind of natural yin/yang symbol. The camera was tilted slightly backward at the moment of exposure, with the result that the barn and some vertical lines such as fence posts incline on a slant parallel to the shadow line. The effect of this is that the scene is entirely natural, almost ordinary, and yet somehow distorted and unreal.

Beyond these technical aspects, this photo does indeed contain emotion and spark emotions. There is always something poignant in seeing an old picture of people, probably because we know that the people within the photo did not remain the same--no, could not remain the same, and neither can we. That this is an "old picture" also plays an additional role. The late ex-Beatle George Harrison commented that listening to an old record was more than just hearing the tune's melody, that we also hear how people sang in that era, how microphones sounded then, and even how phonograph recordings themselves were styled. The print of this photograph is black and white, and it has plain white borders. With its time stamp, AUG 68, along it's top border, the entire thing looks just as we know photographic snapshots looked when they were printed in those days, August of 1968, a time nearly 38 years in the past now, a time that fades further into the past as each day passes.

Look at candid photographs made by Walker Evans, Robert Frank, the early (B&W) Joel Meyerowitz, Gary Winogrand and others, and you will see in much of their work many of the same characteristics as found in this snapshot, and its relaxed, unrehearsed, unpretentious appearance. How many other evocative snapshots are hidden away in shoeboxes and photo albums? As people who "read" photographs, we will be fortunate if others like this one are found, digitized and displayed electronically so that we can find them.

1 Comments:

Excellent blog!!

Post a Comment

<< Home